We met – we married – a long time ago

We worked for long hours – wages were low

No telly, no radio, no bath, times were hard

Just a cold water tap and a walk up the yard.

No holidays abroad, nor carpets on floors,

But we had coal on the fire – we never locked doors

Our children arrived — no pill in those days

And we brought them up without State aid.

No Valium, no drugs, no L.S.D.

We cured our pains with a good cup of tea.

If you were sick you were treated at once,

Not “fill in a form and come back next month”.

No vandals, no muggings, there was nowt to rob,

In fact, you were quite rich with a couple of bob.

People were happier in those far off days,

Kinder and caring in so many ways.

Milkmen and paperboys used to whistle and sing

And a night at the “flicks” was a wonderful thing.

We all had our share of trouble and strife,

But we just had to face it, that was life.

But now I’m alone and look back thru the years.

I don’t think of the bad times, the trouble and tears

I remember the blessings, our home and our love.

We shared them together and l thank God.

Chapter 1 – Introduction

I laid in the cold, dark room, suddenly wide awake with the sensation that something was going to happen very soon. Our neighbour had just roused my father, who had been lying on the top of my bed, having a quick rest. They had hurried outside and I heard the slamming of the front door.

l wrapped myself in my nylon quilted dressing gown, as I was already shivering with anticipation and went to sit at the top of the stairs. The flight was steep and narrow and looked down onto the narrow passageway that led to the front door. The living room door was visible and I could see the embossed pattern on the wallpaper glistening in the moonlight that shone through the back window. l could hear murmuring from the front room that was situated to the right, off the passageway. Then as my senses heightened l could hear the harsh breathing and cries of pain from my mum and the soothing tones of our neighbour, Mrs Ann Barnett.

Soon dad was back with the midwife, who quickly took charge of everyone. To this day I still do not know why they need so much boiled water but l guess it gave my dad something to do in the kitchen – away from “women’s” things.

It seemed like an eternity, shivering at the top of the stairs, forcing myself to stay awake while my sisters slept soundly in their beds. Sitting in the cold and dark l could see my breath waft gently from my mouth in pale grey wisps. Aimlessly I emulated the glamorous movie stars that l had seen on the television. I slowly crossed and uncrossed my legs in an elegant gesture and made exaggerated movements with my hands pretending to smoke a cigarette. This was accompanied by the occasional toss of the head and pout of the lips. Eventually, the wait was over and I heard dad leave with the midwife and our neighbour. Slowly I crept down the stairs.

I laid in the cold, dark room, suddenly wide awake with the sensation that something was going to happen very soon. Our neighbour had just roused my father, who had been lying on the top of my bed, having a quick rest. They had hurried outside and I heard the slamming of the front door.

l wrapped myself in my nylon quilted dressing gown, as I was already shivering with anticipation and went to sit at the top of the stairs. The flight was steep and narrow and looked down onto the narrow passageway that led to the front door. The living room door was visible and I could see the embossed pattern on the wallpaper glistening in the moonlight that shone through the back window. l could hear murmuring from the front room that was situated to the right, off the passageway. Then as my senses heightened l could hear the harsh breathing and cries of pain from my mum and the soothing tones of our neighbour, Mrs Ann Barnett.

Soon dad was back with the midwife, who quickly took charge of everyone. To this day I still do not know why they need so much boiled water but l guess it gave my dad something to do in the kitchen – away from “women’s” things.

It seemed like an eternity, shivering at the top of the stairs, forcing myself to stay awake while my sisters slept soundly in their beds. Sitting in the cold and dark l could see my breath waft gently from my mouth in pale grey wisps. Aimlessly I emulated the glamorous movie stars that l had seen on the television. I slowly crossed and uncrossed my legs in an elegant gesture and made exaggerated movements with my hands pretending to smoke a cigarette. This was accompanied by the occasional toss of the head and pout of the lips. Eventually, the wait was over and I heard dad leave with the midwife and our neighbour. Slowly I crept down the stairs.

I peered around the door of the front room and felt the immediate warmth from the fire – now just glowing embers. Mum was lying in the bed which had been brought downstairs towards the end of her pregnancy when it was too much effort for her to climb the steep flight. She looked very pale, with dark circles under her eyes. Her dark hair clinging to her scalp was the only sign of her struggle. She sensed someone was there and slowly opened her eyes and smiled. “Can I see?” I asked and she proudly pointed to the crib by the side of the bed. Rushing across the room I looked into the crib in eager anticipation. “Ooh” I gasped wrinkling up my nose as I stared down at the baby in the crib “It’s a Chinese baby” With his bright yellow skin, a shock of black hair that was sticking up on end and his wizened, screwed up face he looked just like an old Chinese sage.

Mum smiled and said, “He looks funny now because he had a hard time coming into this world. We are lucky to have him, if it had not been for the skill of the midwife we would have lost him”.

My brother Stephen had been born three weeks overdue, jaundiced and almost strangled at birth by an exceptionally long umbilical cord. Today, of course, home births are a rarity. Most take place in hospitals monitored by machines and nurses. When I was born the midwife was an integral part of the delivery process. In my mum’s day, however, things were very different and this is the tale she tells about her beginnings and childhood in the East End of London in the nineteen twenties.

Samantha French (nee Sheila Allen) Lucy’s daughter

The following story was recalled to Samantha by Lucy in 1995.

Me (Samantha French) Mum (Lucy) and Doreen (Ivy’s daughter) hopping at Yalding in Kent in later years.

Chapter 2 – Arrival

When your time had come the local “baby lady” was on hand to help with the delivery. This person would have no formal training but if your pregnancy and birth were without difficulty, she would help deliver the new child safely. However. if serious conditions prevailed, more often than not the child and sometimes the mother died at childbirth.

Times were tough for the poor. not only did women bear more children due to lack of contraception but they were unable to afford proper medical care. Poor nutrition and the fact that they got no relief from looking after home and family for the nine months made childbearing a hazard. Little wonder the mortality rate was high.

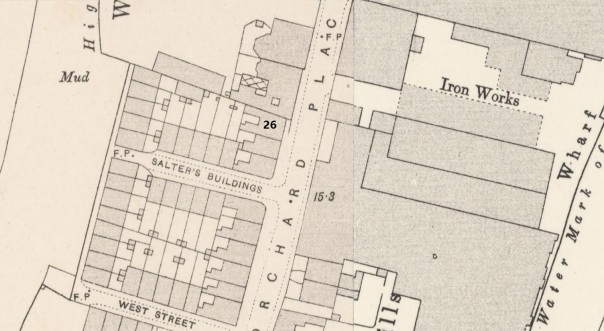

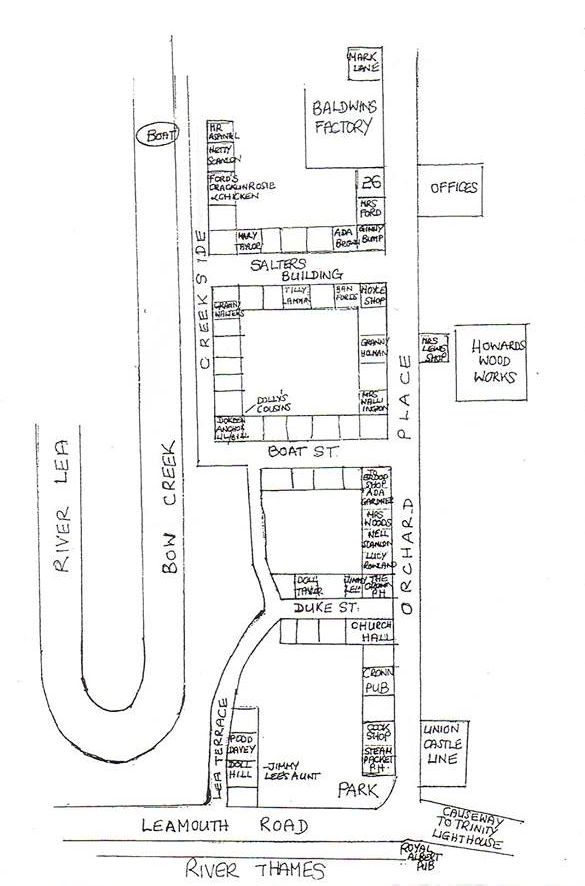

On the 23rd September 1924, 26 Orchard Place, Bow Creek in East London was abuzz with the confinement of my mum Louisa Jesse Taylor. I was to be her sixth child so she knew exactly what to expect. She had returned two days previously from the annual Eastend exodus to the Kent hop fields. The other children sensed her time was near. Bill my eldest brother was in a residential home for the crippled, he had fallen downstairs as a small child and broken his hip. He was taken to Whipps Cross hospital. He was in the hospital for nearly two years, with little supervision to the healing process. As a small child, he wriggled too much whilst in traction and as a result, the bones fused incorrectly. He was left with one leg an inch and a half shorter than the other. Mum discharged him from Whipps Cross and took him to Balem St hospital, but it was too late to do anything about it. As he grew bigger Mum was no longer able to care for him at home. My eldest sister Ivy lived with Granny Nichols my Mum‘s Mum. It seemed to be the custom of that time for the eldest child to live with the Grandparents. I guess it enabled the mother to return to work or just made room for others or else the baby had been born out of wedlock. Maggie and the boys Alfred (known as Giggy) and Steve, however, knew it would not be long before they had a new brother or sister.

Mrs Esther Woods the “baby lady” was on hand. Actually Esther Woods did more than deliver babies. She was the person you turned to with any medical problem. She was the local “mother” figure who had a remedy for all ills. She had no medical training but had a natural instinct for caring. Her common sense remedies passed down through generations usually helped and she always knew when a problem was outside of her control.

Esther Woods had brought many of the children of Bow Creek into the world and was well prepared to assist in my arrival. When the contractions were coming every few minutes

Mum took to her bed and Mrs Woods hung a towel to the top of the bed. When her body was racked with pain Mum would grab hold of the towel pulling it towards her mouth to relieve the tension and biting on it to stop herself from crying out in agony. There were no drugs available to ease the pain and she had never been to classes to teach her to “breathe properly”. This was natural childbirth in the raw. I came into this world with a struggle that left my poor Mum exhausted. A massive 14 pounds, I had been a difficult labour. But thanks to Esther Woods‘ skills I was delivered safely and my Mum did not require any further medical treatment. My lusty cries for food ensured my Mum did not get a rest straight away, but once sated we both slept peacefully. Despite the relative “cheapness” of breast feeding this was not common practice at that time. For one thing these folk lacked the nourishment to provide good milk and secondly it tied you too much to the baby. Once born babies were often left in the care of older siblings while mothers got on with their work. Consequently most babies were reared on diluted Carnation milk, so it was no wonder they looked so chubby and had such a sweet tooth. The next day it was back to normal for my Mother. Fathers had no role in childbirth, that was women’s work, even in normal circumstances, but it was going to be awhile before my dad, Stephen Wallace Taylor saw me as he was currently being detained at His Majesty’s pleasure on the Isle of Wight.

Lou and Steve as they were known were married in 1911 when Lou was seventeen. She had been captivated by his good looks and charming manner. but those same qualities were to be his downfall. Ever the ladies’ man he was forever being pursued by women and he took full advantage of this. Although very poor you would not know this by his outer appearance. He always wore a suit. but underneath the shirt was only a bib front. His shoes would be so highly polished you could see your face in them, yet the soles would he held together with cardboard. He was known locally as the “Kerbstone Millionaire” because although he had nothing he carried himself as a man of substance. Striding down the street. whistling a jaunty tune, he was a striking figure at 6′ 3″ with dark wavy hair. Even more distinguishing was the fact that he had lost the top of the index finger on his right hand. due to an accident at work. This too was to prove his downfall.

He and Lou had argued some time earlier and he had left the home they were sharing in Siivertown, taking Maggie with him (he called her Moggers). He had gone to stay with his sister in Orchard Place. His sister Lou Brown had arranged a reconciliation between them and through this Lou, Steve, the boys and Maggie all moved into the front bedroom of 26 Orchard Place, a home owned by Mr & Mrs Jock Reid. Following the reconciliation I was conceived.

Not in work at this time, he used to go to Hoxton in North London and hang about with all sorts of villains. He would also go to Chinatown to play Pukker Poo (a type of gambling game.) lt, therefore, came as no surprise that he ended up in trouble. In his desperation to make some money Dad had got involved in some confidence tricks. He had gone to two different women in East Ham, claiming he was of friend of their husbands. After winning their confidence he then said he had been asked to collect a couple of pounds from them to take to the husband. The women freely handed him the money but later reported the incidents to the police when they discovered they had been tricked. Having furnished the police with very accurate descriptions of Dad it wasn’t long before he was picked up. In court, with Mum five months pregnant with me and four children to support, he was shown no mercy, considering this was a first offence. He was sentenced to three years in Parkhurst Jail on the lsle of Wight. Even the victims expressed their sympathy to Mum, but hardship was nothing new to her so she struggled on alone. I was a year old before he first saw me, when Mum took me on one of her rare visits to the Jail. He was set free after 2 years for good behaviour, but prison life saw the start of his ongoing battle against gastric illness and ulcers.

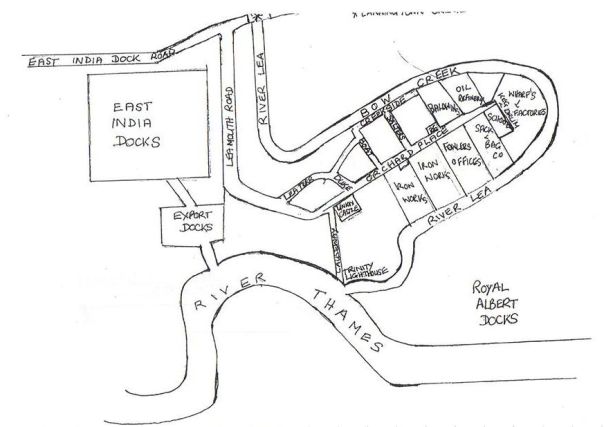

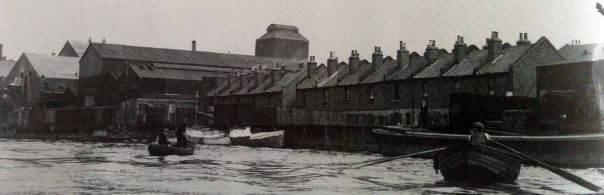

The Orchard House, which was where we lived, was part of a small enclave in the loop of the River Lea. As the river, which rises in Bedfordshire, nears the Thames it forms a horseshoe shaped loop called Bow Creek, before discharging itself into the Thames near Blackwall. A community was formed within the loop in the early 1800’s. The River Lea was used from Roman times to enable them to colonise such places as St Albans and Luton. One of the earliest references to Bow Creek was recorded by John Speed. cartographer and historian, who states:

The Orchard House, which was where we lived, was part of a small enclave in the loop of the River Lea. As the river, which rises in Bedfordshire, nears the Thames it forms a horseshoe shaped loop called Bow Creek, before discharging itself into the Thames near Blackwall. A community was formed within the loop in the early 1800’s. The River Lea was used from Roman times to enable them to colonise such places as St Albans and Luton. One of the earliest references to Bow Creek was recorded by John Speed. cartographer and historian, who states:

“in the year 896 the Danes. after landing on the Essex coast sailed up the Thames to a place on the River Lea called Bow Creek, continuing afterwards to Ware in Hortfordsltire. Here they erected a fortress. King Alfred. in order to dislodge these “strolling thieves” from their new quarters, cut off supplies and provisions from the enemy by land and at the same time diverted the current of the Lea into 3 channels: “Soe that where shippes before had sayled now a small boate could scarcely rowe” thus preventing the return of their fleet to the Thames“.

A whole series of navigational canals and reservoirs were built from it over the intervening years. Until the advent of proper sewerage and water treatment the Lea would discharge all the human waste and gruesome waste from the butchering trade, directly into the Thames. Now through its reservoirs and treatment plants it supplies one Sixth of London’s water supply.

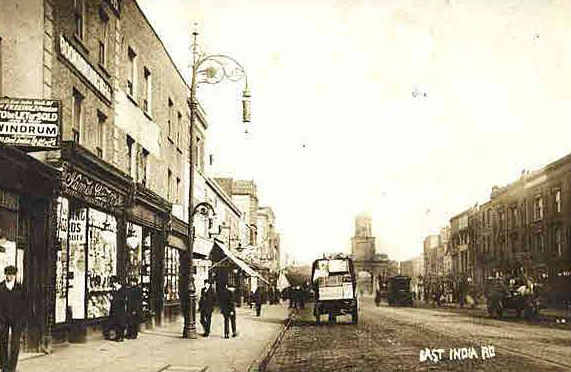

Entrance to this little known backwater of Poplar, lying east of the East lndia Docks, is gained from Leamouth Road just before the Canning Town bridge. Leamouth is derived from Laymouth House which had stood in this part of the hamlet since before the 17th century. In 1675 Thomas Joyce, citizen and clothmaker of London, leased to Anne Webber of Blackwall “all that messuage of tenement and all gardens, orchards, lands, meadows and pastures commonly called or known by the name Laymouth”. The property was estimated to cover approximately 11 acres. In 1697 the area was referred to as “Orchard House” after the development of the old house, from which they built the offices for the Union Castle Line and development of the orchards and gardens. Little was recorded of the area until the early 1800’s. (Tower Hamlets News – April I969)

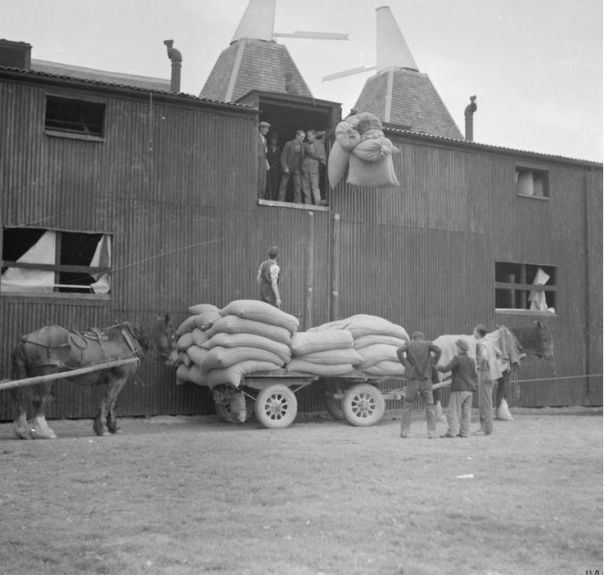

Laws were passed by parliament some time ago which decreed that the River Lea would act as a boundary for polluting industries. which could only operate east of its shores. Consequently a glut of chemical, paint factories and gas works formed a barricade, this being the closest they could get to the City of London. The area was dominated by a number of factories which included Trinity House corporation, Thames Plate glass company and Fowlers syrup and treacle plants. Many thriving ship building establishments were listed as working from ‘Bow Creek which included Miller, Ravenhill and company, Ditchburn and Mare, George Joseph Gladstone, Benjamin Wallis, Jacob and Joseph Samuda and Richard Green ship owner. The Thames Iron and Shipbuilding company which started in I846, having taken over the then insolvent Ditchburn and Mare, was situated on Bow Creek. This however closed in 1912, having completed over 500 destroyers and frigates. The last ship to leave the yard was the HMS Thunderer in 1911. The Bow Creek coal wharves served as a depot to supply the surrounding factories with their much needed fuel.

Orchard Place was built between 1829 and 1845 at the time when many of these companies were operating from Bow Creek. At one time about 75% of the inhabitants of Orchard Place were employed at the “Glass House” (Thames Plate Glass co). Here plate glass was made and sent all over the country. The glass for Crystal Palace was made here. Around 1875 due to the emergence of America as the predominant glassmaking country, many Bow Creek folk migrated to New Albany, Indiana, the USA to do similar work. Many descendants of the glassmakers still lived in Orchard Place during my time there. The most numerous being the Lammins. Scanlons and the Jeffries, who had intermarried. The predominant factories during my time were Messrs Baldwin (who still had some of the Glass House walls), Bow Creek Union Oil Mills, Fowler’s sugar refinery and the Thames Sack and Bag company.

Surrounding the area were the Royal Albert and East India Docks. The march of the Empire which had inspired the construction of the East India Docks in 1806, was coming to a halt. By 1920 the docks were run down and neglected. They still harboured ocean-going and coastal vessels and some Eastern cargo was still handled there, but the docks were too small and too much out of date to be worth modernising. On the left of the entrance was a building known as the Pepper Warehouse. This was a store for the sailing vessels in the dock. After the decline of the Steamers, it was taken over by the LNE railway. Behind the shabby warehouses and scummy waters there lay a history unsurpassed anywhere else in the Port of London Authority. Many pioneers had set sail from its ramshackle basins, intent on colonising the new lands. They were mainly family groups who went into the unknown equipped with little more than courage. It had been the dock for all the great Clippers including the Cutty Sark. Its eerie wharves and warehouses could tell many a gruesome tale. Orchard Place was built between 1829 and 1845 at the time when many of these companies were operating from Bow Creek. At one time about 75% of the inhabitants of Orchard Place were employed at the “Glass House” (Thames Plate Glass co). Here plate glass was made and sent all over the country. The glass for Crystal Palace was made here. Around 1875 due to the emergence of America as the predominant glassmaking country, many Bow Creek folk migrated to New Albany, Indiana, the USA to do similar work. Many descendants of the glassmakers still lived in Orchard Place during my time there. The most numerous being the Lammins. Scanlons and the Jeffries, who had intermarried. The predominant factories during my time were Messrs Baldwin (who still had some of the Glass House walls), Bow Creek Union Oil Mills, Fowler’s sugar refinery and the Thames Sack and Bag company.

Surrounding the area were the Royal Albert and East India Docks. The march of the Empire which had inspired the construction of the East India Docks in 1806, was coming to a halt. By 1920 the docks were run down and neglected. They still harboured ocean-going and coastal vessels and some Eastern cargo was still handled there, but the docks were too small and too much out of date to be worth modernising. On the left of the entrance was a building known as the Pepper Warehouse. This was a store for the sailing vessels in the dock. After the decline of the Steamers, it was taken over by the LNE railway. Behind the shabby warehouses and scummy waters there lay a history unsurpassed anywhere else in the Port of London Authority. Many pioneers had set sail from its ramshackle basins, intent on colonising the new lands. They were mainly family groups who went into the unknown equipped with little more than courage. It had been the dock for all the great Clippers including the Cutty Sark. Its eerie wharves and warehouses could tell many a gruesome tale.

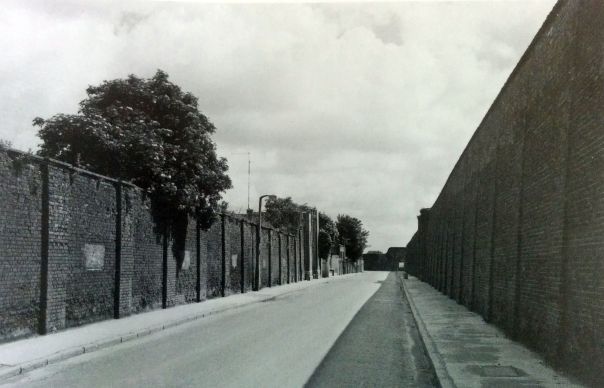

Dockers throughout history were notorious thieves. To try to combat this and minimise the enormous losses suffered by the shipping companies when the London Docks were built on marshy land to the east of the city, they were surrounded by high, prison-like walls. There were only certain entry and exit points where all personnel could be stopped and searched. The great high walls built to prevent pilfering, on either side of the Leamouth Road, which led down to Orchard place, gave it the nickname “Down the Wall”.

Leamouth Road (formerly Orchard Street) looking south from East India Dock Road.

Leamouth Road (formerly Orchard Street) looking south from close to Orchard Place.

This was one of the poorest areas of London. There were no butchers, bakers, barbers, post office, police station, fire station or pawn shop. Neither trams nor buses came to the neighbourhood and for the most part, it was unheard of by many including those who lived nearby in Poplar. There were about I00 terraced houses, stretching out in an endless procession, as like as peas in a pod, with no individuality whatsoever. The houses were all two up, two down terraces. with a scullery and washroom outback.

Each front window was draped with a lace curtain, looped back sufficiently to reveal an aspidistra in a pot. Each front door was exactly the same and they all had their own front step, whitened with chalk. The houses were all huddled so closely together that there was little or no privacy and with only a small patch of dried up earth enclosed within a five-foot brick wall. Neighbours lived cheek by jowl, forever looking out upon the world of bricks and mortar. The backyard was a depository for anything that could not fit into the small house. It might contain a zinc bath, copper boiler, clothesline, washing board, rabbits. racing pigeons or chickens.

In addition to houses, the area contained three pubs the Royal Albert, the Crown and the Steam Packet, Bow Creek school, a small church and a few comer shops. The rest of the space was taken up by the factories.

Around these streets, my Mum pushed her bassinet (a huge black pram with shiny silver coloured wheels) with me wrapped in a long nightgown like robe Iying in the back and Giggy sitting in the front, with Maggie and Steve running alongside. The shop on the corner of Salters building was owned by Mrs Moyce. She sold everything in the grocery line and her shelves would be packed with dusty boxes and tins of assorted colours and shapes. It was a wonder she could find anything as the store was so cramped, but she would always go straight for whatever you wanted. Mrs Moyce runs a “book” for the benefit of the local families. This meant that when they bought anything from her shop they didn’t pay for it at the time. She would note down the purchases under each household’s name and then at the end of the week she would tot up the page. If you were lucky and your husband had been paid you settled up. For the less fortunate she allowed extended credit and people paid off as they were able.

The shop on the comer of Boat Street was owned by Mr Joe Brood. He sold more or less the same things as Mrs Moyce but serviced 21 different sets of households with “tick”. Opposite Mrs Moyce was Mrs Levi’s shop where she sold mainly greengrocery items.

The church on the corner of Orchard Place and Duke Street was only used for Sunday school, scouts and brownies meetings. For weddings, funerals and christening, the locals used All Hallows church on the East India Dock Road. Religion played a very small part in the life of the average protestant east ender. There were, however, certain rituals that had to be obeyed that required a minister’s presence. All babies had to be christened within 3 – 6 weeks of birth, not to do this would be considered very unlucky, as the baby would retain its “original sin”. Weddings too had to have the church’s blessing and funerals required the final sanctity of God. For the rest of their lives, the locals would have little contact with the church. So it was with little religious fervour. but more from a sense of duty that I was christened at All Hallows church. The traditional christening gown of cream silk and lace was one that had been passed around the community and was used for all christenings. When not in use it would sit on the shelf at the pawnbrokers. providing a few extra pence for the owner. My godparents were Lucy Rowland and Tilly Larnmin after whom I was named.

There was something constantly buoyant about the waterside parishes in spite of their poverty. Due possibly to the proximity of the river, the presence of ships. sailors. chandlers shops. rope and canvas makers plus the smell of tar and the Thameside mud with the hint of distant parts. The area was a unique working community, everyone equal in their poverty with a shared pride and sense of humour. It was in this environment that I lived contentedly with my brothers and sister for 11 years. My Dad, after his release from jail, became a flower seller in Rathbone market, one of the several famous street markets that were patronised by the citizens of East London. Each day he would rise very early and walk to the top of Leamouth Road, where it meets the East India Dock Road, in order to catch the early tram to Covent Garden. There he would buy his flowers and then return to set up his stand in the market. As poor as the people were in that area some would manage to save a few coppers in order to buy bunches of flowers for their homes or to place on the graves of loved ones. With very few homes having gardens and little greenery around it was a welcome treat. Dad specialised in making carnation buttonholes for men’s beanos and outings. He would also make and sell rosettes and ribbons for the Oxford and Cambridge boat race and other such events.

The men who worked in the local factories would break the dull routine of their lives by organising a “Beano”. They would hire a charabanc (they were never called coaches) and take off for the day to Southend on Sea or maybe the Kent coast or countryside. This was a joyous occasion and would cause much excitement in the community. Crates of stout would be loaded onboard and all the men would wear their buttonholes with pride as they clambered onto the charabanc for their special treat. They would leave from outside their factory and as they boarded all the local children would rally around. The kids would call out “throw us yer mouldies” and as the charabanc pulled away the men would throw pennies to the children. There was a scramble for their share and it was rare that a child didn’t get a coin.

The men would swap tales and jokes on their journey to the coast – relishing their freedom from work and home. Once the drinking started community singing would begin. At the resort, they would do all the normal touristy things for that time. In Southend, which is situated at the mouth of the Thames Estuary, they would visit the Kursaal funfair and go on the dodgems and play the pinball machines. They would walk to the end of Britains longest pier and eat local seafood like whelks, shrimps, cockles and jellied eels. At the appointed hour they would all board the charabanc for the homeward journey. Relaxed and mellow from their “day off” they would sing their songs with fervour.

There were no family outings for these people, this was a luxury they could not afford. So the men look for the occasional break from work to recharge their batteries. Most men would return in a “romantic” mood helped on by freedom and booze, so many a new baby would be conceived after the annual beano.

Despite these outings, business for my Dad was not good, especially since he had a wife and six children to support. It was this dilemma that prompted to take the drastic action in 1925, of joining the Merchant Navy.

Chapter 3 – The Early Years

During the time that my dad was at sea I enjoyed a happy childhood “down the wall”. I would play merrily with the children in the streets. Lacking any form of sophisticated toys, our games were spontaneous and imaginative. Known as “Locket” by one and all from the nursery rhyme “Lucy Lockett”

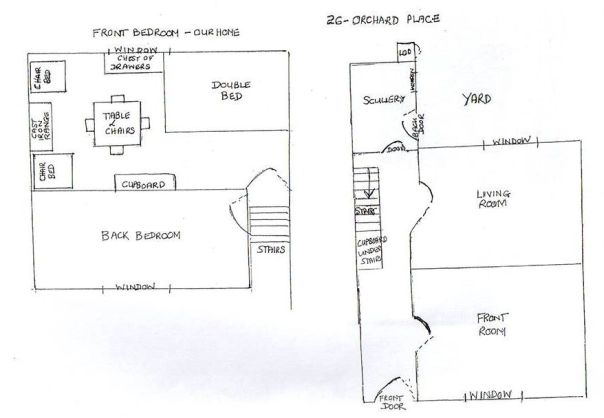

Orchard Place was typical of the houses in that area. We sublet the front bedroom from Mr & Mrs Reid who had the rest of the house. It was quite common at that time to find more than one family sharing at the house, all rooms were used to the maximum, you were very posh indeed if you could afford to keep the front room for special occasions. Our room was a large oblong shape and you entered it on the far left through a door at the top of the steep flight of stairs. Immediately opposite was a double bed. A window centred the back wall and underneath this stood a chest of drawers. A cast-iron range dominated the right-hand wall. either side of which stood at bedchair. A table covered with a piece of oilcloth and four chairs stood in front of this (see appendix ). The iron range would be stoked well during the day to provide warmth and means to cook. At night it would be banked up with cinders and peelings, to be revived the next morning. Pots and pans would hang from the wall. The scullery which contained a larder, a big china sink and the copper boiler was situated downstairs off the back room. Hanging outside the back door would be the hip-sized tin bath, which would be used every Friday, to give us children a good scrub and a hair wash. We shared this and the outside toilet with the Reids.

After Mrs Reid died and Stan was born we took over the back bedroom upstairs as Jock moved his bedroom to the front room. Later as we grew bigger and needed more space we also took on the back living room. A long narrow passageway ran from the front door through to the back. The stairs went up to the right and the front room and living room were off to the left. The scullery adjoined the living room (see appendix).

Despite the crampiness of our living conditions, we were cosy and happy at Orchard Place. Pride of place in our room was a glass Punch Bowl that stood on top of a lace doily on the chest of drawers. Dad had brought this back from one of his visits to sea. I was playing one day in the room, while mum was down in the scullery doing the laundry, and had made a swing by tying a string from the bedpost to the chest of drawers. l sat on this makeshift swing and in my excitement pushed harder and harder. Suddenly the chest of drawers tilted forwards causing the swing to collapse and the Punch Bowl to fall. Fortunately, the main bowl and most of the glasses landed on the bed, but some glasses fell onto the floor and were broken. Terror-stricken I dashed under the bed as Mum raced up the stairs to find out what all the commotion was about. She tried to poke me out from under the bed with a broom. but l was transfixed in fear. Then she tried coaxing me out. saying she would not punish me if l came out – at this point I meekly crept out from under the bed, only to receive a firm smack on the bottom!

There was an outside toilet in the yard but as it was often too cold to make the long trek. chamber pots (known as pos) were stowed under the beds for nighttime emergencies. On many occasions when I had looked out of the window on hearing a row going on down the street, I would see the man of the house dash out slamming the front door after him. This would immediately be followed by the upstairs window opening and the contents of a chamber pot being thrown down upon his head!

The women went about their work, providing for their families. Monday was always washday and they would boil up their coppers full of water, using anything that they could lay their hands on to stoke up the fire. Using a rubbing board and wringer, with “blue wash” in the final rinse, they produced the whitest whites you could imagine. It was a full day’s work, but the lines of washing proudly blowing in the breeze was reward enough.

Each week they would only wash one sheet at a time from the bed, placing the clean one on the bottom, to help prevent the spread of fleas. The previous weeks bottom sheet became the top sheet, that was of course if you were lucky enough to have both top and bottom sheets.

Tuesday was ironing day, with the flat iron being warmed on the range. This was a mammoth task as the clothes and linen sheets would have to be pressed, wrinkle-free. There were no labour-saving fabrics at that time, no steam irons to help the harassed housewife. Despite their poverty, the people of Bow Creek generally kept their homes spotlessly clean. This was of course out of necessity as if you did not keep the house clean you would soon be overrun with rats, fleas and other nasty insects. It also helped stop the spread of disease. On cleaning days, the women sitting on the window ledges, leaning out cleaning the outsides of their windows would be a regular sight. Resplendent in their overalls and headscarves, they would call cheerily to each other and the kids as they undertook this dangerous task. Brass knockers gleamed and the ever-present white doorstep was a testament to their pride.

A housewife’s lot was not an easy one and it was made more difficult by the need to feed many hungry people, yet have very little money to do it with. They would make their own bread, pastries, suet dumplings and puddings as those were a good means of filling empty stomachs. Mum was always the one to go without when food was short. Often living on bread and lard, she made sure we children never went hungry. In fact, some of the other children would say “Mrs Taylor, can we have bread at your house, as your kids get jam on it ” This would be made after the fruit picking season and eked out throughout the year.

A weekend treat for us Taylor children would be when Mum would walk to Chrisp Street Market on a Saturday evening. Known as “Cristreet” by the locals lt was situated in Poplar, off the East India Dock Road. With only a few shillings in her purse, she would go for her weekend shopping at the market. She would time her arrival with the closing down of the stalls and be able to stretch her buying power to get vegetables, meat, bread and other perishable goods that would be wasted if not sold. A scrag end of mutton for thruppence, three ha’porths of potatoes and a ha‘porth of pot herbs would make it a nourishing meal.

She never forgot us children and always bought us each a toffee apple and a pound of broken biscuits, which would be our weekly treat. She would trudge back with her heavy load at about 10 pm and we would be waiting for her at the end of Leamouth Road, ready to help her carry the bags, excitedly anticipating our special treat.

A word at this point to the uninitiated. At that time you got 240 pennies for one pound, each penny was worth four farthings, two farthings making a halfpenny or ha’penny. Other coins included a thruppence (three pennies), a sixpence and a shilling, this being worth l2 pennies. There was also a florin (two shillings) and a hall crown (two shillings and sixpence). Potherbs incidentally were not a bunch of herbs such as parsley or sage. They were a selection of stewing vegetables such as parsnips. turnips, carrots, leeks etc.

I started school at the age of three and joined the nursery class in Bow Creek school. The school was made up of five classrooms, a hall and a little room used for woodwork and craft. The headmaster was Mr Hayward who ruled the school with a fist of iron. The classes were made up of children covering a two to three year age range. Class one being the nursery class for 3 – 5 years, class two was for 5 –7 years, class three was 7- 9 years, class four was 9 – I l years and class five ll – 14 years. All children left school at fourteen. The average number of children attending the school at any one time was around one hundred and twenty.

The day always started with a prayer and Mr Hayward would then call a “handkerchief parade”, where everyone had to show their hankies. People were very poor and it was a lucky soul who actually possessed a hanky. Some of the children had a piece of rag and before assembly, they would tear these into strips, so that everyone had a piece of rag to display during the parade. On the cry of “Handkerchiefs”, we would hold up our rags and wave them triumphantly

The lessons covered in school involved learning many things by heart. The repetitious reciting of tables and words etched them deeply into the minds of the children. In history we would hear about the glories of the Empire and nature lessons would involve trips to the park or the riverside. Writing was taught letter by letter and it was very important to have the tail of the p and q the exact length and that i‘s were dotted and t‘s were crossed perfectly. Physical education was a ritualistic affair with the children marching around the playground in a goosestep fashion, with a bit of arm swinging. We did not change our clothes for P.E.

We would all go home for lunch as the school was so close. If we were lucky we would get a “doorstep” of bread and jam. After lunch, the nursery class would have to lie down for an afternoon nap. When I first started school I had my dummy pinned to a piece of string and tucked down inside my jumper. As we laid down. I would draw this out for comfort and gnaw happily away at it making loud “yoy yoying” noises. The teachers were not happy with this and soon made me stop using it.

The standard of education was not great, despite having five teachers for 120 pupils. Truancy was very high with children being out of school to help in the home or to go out “jobbing”. Teachers were not too concerned about giving errant pupils a good hiding and received little respect from their charges. The prospects for school leavers were limited, most boys going to work at Baldwins or one of the factories. The main option for girls too was factory work – before they got married and had families of their own.

Children mostly played in the street. They would use the park which was provided by George Lansbury, the first commissioner of works when it was open. It contained three swings, a sandpit and a roundabout. The “parkee” was a Mrs Taylor (no relation) who was a bit of a dragon. She thought nothing of giving the kids a “clump round the ear “ole” if they were cheeky to her.

Their games included hopscotch – the grids being drawn from the chalk collected down the causeway. Tin Can Copper, which was a game of hide and seek. One person threw the can and all the other children had to run and hide. The person would then guard the can and try to catch anyone trying to get back to it. The winner was the first one to get back to the can without being caught or “had”. The victor would triumphantly cry “tin can copper”.

Kiss chase was another popular game. A cry would go up and the girls would dash off. followed in 20 seconds by the boys. If they were captured they had to give the boy a kiss. Funny how the older girls. who in previous games had shown the talents of Olympic sprinters, would in this game run with as much speed as a tortoise!! Kerb or wall was another favourite, with all children standing in the middle of the road when the caller would shout either “kerb” or “wall”. According to his choice, the other children would then dash to the appropriate side of the road. The last one to touch base was “out”.

“Knockdown ginger” was a game of dare that would irritate certain local inhabitants. Children would dare one another to knock on the door of a particularly grumpy neighbour and then try to escape, without being sighted. Gobs played with stones and hoops and tops were other popular playthings.

Having no money for toys the children were inventive. Boys would make cars using an old wheel with a piece of metal or wood shaped like a T, to act as a steering rod. My brother Giggy made a barrow from old wheels and scraps of wood scavenged locally. This was used in many of his “business activities” but he would be happy to sometimes give us girls and younger children rides in it.

Tip Cat was a game where a piece of wood was balanced on a stone like a see-saw and a pebble was placed on one end. The children would take it in turns to strike the other end and see how far they could catapult the pebble. The winner was the one who struck it the farthest distance. Glass knobs from bottle stoppers were often used as marbles. The stems being broken off and the fragmented ends are smoothed with emery paper. In season, conkers would be gathered and endless tournaments would he played.

Life at that time had an innocence that has been lost in today’s “electronic” age. Children had little, but through their inventiveness were always able to entertain themselves. Lack of traffic rendered the streets safe and we would play outside until dark, without fear, coming in only to eat and when it was finally time for bed.

In the summer we all used to go to the causeway and swim alongside the barges as the men replaced the rivets and life on the Thames went on as usual. The waters would be murky and muddy with all sorts of rubbish and rats swimming in them. but we never seemed to notice this.

Early one morning in 1928 Mum got up to rekindle the range and start breakfast for us children as normal. This day, however, she had a nasty surprise awaiting her as she went climbing downstairs. She was shocked to find water coming halfway up the stairs. She ran back upstairs and looked out of her bedroom window, as she opened the curtains she was aghast to see that the whole street was underwater, way past the level of the front doors.

There were some men in a boat who called out for her to wait inside until someone came to get us as it was not known if the river would rise anymore. Evidently, the level of the Thames had risen dramatically that night and flooded the whole of the low lying areas right into the City of London.

Mum called us and told us to get dressed. There was great excitement and I felt I was taking part in a real-life adventure. We all rushed to the window and looked at the once familiar street, now looking more like the Creek. We yelled out to their neighbours who were now also looking out of their windows.

After some time, just as the novelty of being shipwrecked in our own home was wearing off, a boat came to rescue us. It was a large rowboat and men came into the house wearing huge rubber overalls. They plucked us from the dry part of the stairs and carried us out to the boat where they rowed us to a point where the water level was no longer a problem. From there we were all taken into a church hall to dry off and get some food. We had to stay there until the waters fully receded and there was no threat of a repeat occurrence.

The mud residue that was left behind was thick and smelly and had left a nasty tide mark on all the walls. The floors were inches thick with the stuff. The great clean-up campaign had to begin. Fire trucks came and hosed out the worst of the mess and they also cleared the streets and the outsides of the buildings. Then everyone had to take everything out and wash down all the walls and ceilings and their furniture. The wallpaper and some furniture had been ruined and had to eventually be replaced. The government paid a small grant to all those people who had been affected by the floods and this helped to bring our household back to normal.

Chapter 4 – Death of my Father

I was sitting on the doorstep with my friend Dolly Chapman. It had started to rain. The drizzle stopped us from playing outside, so we sat in the open doorway playing a game of gobs. My Mum was bringing in a sheet which she had hung out to dry and was now putting it on a line that she had strung up in the passageway.

We stared open-mouthed as the red Royal Mail van pulled up outside my house. It was rare that one came down our way. The postman approached the door with a telegram in his hand. but before he could hand it to Mum she had collapsed, already sure of what would be written inside. We rushed to number 15 to fetch Mrs Esther Woods who quickly came to help Mum.

The postman, obviously used to being the bearer of bad news handed her the telegram mumbling “I’m sorry Luv” and drove off to his next appointment with doom.

Esther helped Mum into the back room and made her comfortable, the offending telegram being placed on the mantelpiece. After she had made her a cup of lea, the east end cure-all, she asked her if she wanted to read the message. With her voice dull and flat she read the message “We are sorry to inform you that Stephen Wallace Taylor passed away at sea on the S.S. Lochmania on February 1930. The cause of death was peritonitis. A sea burial took place on the same day” She crumpled the message and slumped forward in her seat.

My Dad, as a result of his time in prison, had suffered from ulcers and life at sea had not helped this problem. He had just been happy, however, to have a job that paid a regular wage, so had endured the pains. Mum had dreaded this moment. He had seemed very pale and wan during his last home leave and she had begged him not to return to the sea. He had. however, promised a pal Micky Alexander that he would do one more trip so that Micky too could get a job onboard. He had done two trips to sea taking roughly eight months to complete. The first time was at the end of 1927 and then again in the Autumn of 1928. He promised Mum that this would be his last. Also work in London at the time was not easy to find and the need to provide for his family proved too great a burden. He left London in February 1930 but three days out into the Atlantic at 4 pm he died and was buried half an hour later. It transpired that his brother-in-law Joe Butler was on the same ship, however, he refused to go to Dad’s burial claiming he was Catholic and Dad a Protestant. After that voyage was over Joe refused ever to go to sea again, saying he was not going to “succumb to a watery grave”

Bill was working in service in London, Ivy was living with Granny Nichols and Maggie was nearing the end of her time in school, but she still had Steve 10, Giggy 7, me 5 and Stan 3 to support. In those days there were no welfare state or widows pensions to help people like Mum. They had to fend for themselves.

If she wanted to get government help she would have to call in the relieving officers. Made heartless by the harshness of their job, they would come into your home to make an assessment. First, you had to sell all personal possessions. Mum had very little other than basics but was forced to sell what few trinkets my Dad had given her, the mementoes of their life together. She was left with a table and chairs and their beds. Luxuries, as they considered them, such as wardrobes and sideboards had to be sold.

As Mum was only 33 it was considered that she was young enough to work and support herself, so the three older children Steve, Giggy and I were to be sent to a council-run home. Hutton Residential School at Shenfield in Essex. Originally they were going to send Maggie but changed their minds. Maggie remained to look after Stanley rather than have him put in the home too. So instead of finishing her education, Maggie became a surrogate mum to Stan, who followed her like a shadow everywhere she went.

Mum was heartbroken, not only for the loss of her husband and the disposal of her possessions but for having her children placed in the cold, unfriendly atmosphere of a council home. Now, more than ever they needed each other for comfort.

At first we were taken to Langley House, an old ladies home in the East India Dock Road. Here they gave us jelly and custard to settle us. It seemed to me it real treat and I was enjoying the adventure. Mum tried desperately to explain what was happening to us but only Steve had an inclination of the enormity of the events. Dressed in our best outfits with a little bag containing the rest of our belongings, we waited for the car to come and take us to the home. I thought we were going on some sort of holiday by the way my Mum had tried to explain what was happening and as I had never had one before I couldn’t understand why Mum and Maggie kept crying so much. Trying to reassure her I said, “Don’t worry mum I’ll be a good girl, I won’t get into any trouble promise”. This only seemed to make matters worse. Mum started squeezing me so tightly, I could hardly breathe and I felt her warm tears trickle down my neck.

My Mother stood staring at her pretty little daughter with her straight blond hair coming down just below her ears, with a fringe framing her round face. Startling blue eyes stared back at her earnestly, so brave in her innocence. It was tearing her apart to part with us but she was powerless to do anything else. The car arrived and Steve, Giggy and I clambered in, full of excitement not realising what lay ahead during our years at the Hutton School.

It took a while for us to understand that we had been sent away and would not be going home and we never figured out why. All we knew was that we missed our Mum and we couldn‘t understand what we had done wrong for us to be punished in this way.

In the home, I was even further isolated as I had to go to the girl’s dormitory, whereas Steve and Giggy were together in the boy’s dorm. l would briefly see the boys when we were at school. Steve would try to keep me up to date with any news he had of home and Giggy would try to cheer me up. When she could Mum would send a letter and a few sweets for us to share. She got these from the Clarnico Sweet factory where she worked, having sewn a small pocket into her knickers, she would, when the opportunity arose, fill it with goodies to send to us.

To say the place was run on Dickensian lines would be an overstatement. The regime, however, was not conducive for sad and lonely children who were either orphans or who were separated from their families in tragic circumstances. Nurse Rhoda was particularly strict and put fear into most children’s hearts.

At night in the loneliness of the dormitory, I would join the silent weepers. I would cry for my dear Mum whom I missed so very much, for my home, my family, my friends and the freedom of living in Bow Creek. This pleasure was so hard to lose and I longed to be able to run, once again, barefoot in the streets and to be able to break out into a song or dance whenever the mood took me. The regime in the school was very rigid and my bubbly and spontaneous nature often got me into trouble.

One incident I recall was a time when we were seated in the dining hall awaiting the start of dinner. Before the meal could begin all the children had to rise and say ‘Grace’. At that point, the girl next to me had said something to me and I had replied. The Matron screamed at me for talking during “Grace” and insisted that I saw her after the meal for my punishment. The meal was tasteless as fear gripped me, wondering what was going to happen to me.

That night it was Cinema night and a movie was screened for the children’s entertainment. I was not, however, able to watch it. Instead, I had to put on a clean pinafore and while all the other children were watching the film, I had to clean my shoes, without making a mark on my pinafore! As a scared six-year-old l sat surrounded by shoes and started to polish away, afraid I would be punished further if I did it wrong.

Fortunately, not everyone in the home was so cruel and an old housekeeper helped me to get them finished. She put an old rag across my pinafore to ensure it stayed clean. Mum only managed to make one visit when we were all there together as the fare to Shenfield was too expensive. She kept in touch through letters to Steve. The school at the home was more structured than Bow Creek and Steve who had always been “bookish” was able to fulfil some of his potentials. Giggy hated it and learned very little. but the two years I had there gave me a basic grasp of the 3 “R’s”. The boys went on a camping trip for a weekend once and l did a trip out with the brownies.

Mum was working full time in the Clarnico Sweet factory in Cable Street, Poplar but knew she would never get us back without having someone to support her. Her saviour came in a former boyfriend Johnny Marks. He had been Mum‘s first boyfriend when she was sixteen, but though he professed undying love, she couldn’t get serious about him as he was only 5ft 1ins and she was 5ft 7ins. She couldn’t see herself married to a shorter man. Johnny was persistent in his admiration for Lou, as he called my Mum and never gave up trying until she met Steve, who at 6ft 3ins met all her expectations. After a short romance, Mum and Dad married when she was l7.

Disappointed that he had lost the love of his life, John Marks went to sea to find solace. He had the initials I.LL.N. (I love Lou Nichols) tattooed across the fingers of both hands. to remind him of the girl he loved and lost. He left his ship in Australia and from there he got work plying the coastal waters of Australia. If he was in port when a ship docked from the UK he always dropped by in case there was anyone on board that he knew, who could give him news from home. When the Lochmania arrived he learned about Steve Taylor dying at sea. All he could think about was that poor woman back home, whom he still loved and who obviously needed someone to care for her. He took Steve’s job on the Lochmania and returned to London. He paid his respects to my Mum, renewing their friendship. He started getting more local work and saw my Mum on a regular basis, helping out all he could. Mum had always had a soft spot for Johnny, so happily accepted his proposal of marriage. They married in I931 as soon as they were able.

Upon her marriage, Steve and Giggy were able to leave the home after 18 months. I was once more alone. but I was a friendly optimistic child with a cheerful, cockney character which enabled me to survive the ordeal.

I recall the time my Mum brought Johnny Marks to the home and introduced him as my new step-father. They had collected me from the gatehouse and taken me on a single-decker bus to Brentwood. He had brought me a little china tea set as a gift, but all I was really interested in was when were they going to take me home. They said it wouldn‘t be long now and then we would once more he one big happy family. I was feeling quite glum as l went back to the dormitory, sad to have to say goodbye to them once more. When I got back my friend, Mary Arrowsmith, who slept in the next bed admired my teaset and said “I wish I had a Mother and Father like you to pay me a visit.” Mary was an orphan and l realised then just how lucky I really was. Soon I would be able to leave the home and join my family whereas Mary had no one and nowhere to go. Realising life wasn’t so bad after all I gave Mary my tea set.

Once they had you in their clutches, the council were very reluctant to let you go. They had stipulated that l could not go home until I l had my own bedroom. This was impossible under the circumstances in which we lived. Thankfully, Ivy, my elder sister had since married and was able to make up a bed for me in her house. This satisfied the local council and I was allowed out. Of course, I went back to Orchard Place and not to lvy’s. So after two years, the family were once more reunited and life “down the wall” began to regain some normality.

My Mum (Lou Taylor) and my sister (Ivy Taylor) in later years.

Mum and Johnny had two children, Bertha Agnes, a really beautiful child and John born in I934. Bertha, however, died at age 8 months. She had bronchitis and was taken to hospital. Whilst there she caught measles and was moved to an isolation hospital. It was January and bitterly cold and after this, she caught pneumonia, from which she died. It was a tragic death that should have been avoidable. Her funeral was a solemn affair, her tiny white coffin being placed in a glass carriage, that was pulled by a solitary black stallion. Mourners walked alongside accompanying the coffin to the East London cemetery.

Mum went into St Andrews hospital, at Bromley by Bow to have John. While she was away Johnny looked after us. It was during the depression and he had been unable to get a ship. He would make faggot stew which we hated. but ate as there wasn’t anything else. He tried his very best. but he was not used to looking after such a crew. We were thrilled to get our Mum back again and were glad when work prospects improved and Johnny was able to get a ship and once again Mum was in charge.

Chapter 5 – Outings and Treats

Despite our poverty, we children of Bow Creek had a number of treats and outings that we could go on, for the older kids especially the boys these were not so exciting. They could even be considered “cissy”, so they would either not bother to go, preferring to go “jobbing” or would hang about locally. If they had to participate, they would display their contempt, at least to their peer group. Secretly though, they too enjoyed themselves. But were too hard to let their feelings show.

For the younger kids and the girls though, the treats and outings would be looked forward to with gusto. The weeks before an event would see the streets electric with excitement as were the weeks that followed the treat, during which every moment of the day was relived and reviewed with pleasure.

One school trip that was a highlight of the year was a visit to Horsham, Surrey. Mr Hatfield. a dear character and benefactor, would open up his great house and gardens to the children of Bow Creek School. He would send charabancs which would transport the children, accompanied by much singing and laughter, to his house. As part of the treat he would have a small funfair on the grounds and a boat on the lake in which we could all take turns. The children were allowed to run freely in the extensive grounds, which for city-bred kids was an adventurous experience. The sight of acres of green fields. flowers and trees was a real novelty for us compared to the drab surroundings which we were used to.

l am not sure if we ever really appreciated their aesthetic beauty but it was great to smell the fresh air and to be able to run wild on the soft grass and to climb the trees. We were never envious that Mr Hatfield had all this and we had nothing, we just relished the opportunity of sharing it with him for the day. One year I was in a punt on the lake with my friends and as we passed under a bridge, I thought I would reach up to see if l could touch the bridge. Unfortunately, I was able to reach the bridge and as we passed underneath l grabbed hold of the edge and was left suspended in mid-air as the punt silently glided ahead, leaving me dangling from the bridge. The squeals from the other children alerted the punt pole pusher, who with much annoyance turned back to get me, I was already afraid that my arms were going to give way making me fall into the cold water and I then received a sharp telling off from the boatman. This did not, however, sour my image of the day and I became a bit of a folk hero as the tale grew more outrageous after each telling.

A home treat would be on the occasion when the “jampot ride” appeared in Orchard Place. Several times a year a man would pull his cart “down the wall” on the back of which would be a little roundabout swing. A metal pole with seats on each end which went round and round. If you gave the man an empty jam pot – he gave you a free ride. The hoarding of jam pots in anticipation of this treat was a regular pastime for all of us children.

One treat I missed was the school outing to Theydon Bois, part of the great Epping Forest. My friends Mary Taylor and Nellie Scanlon and l had decided to play truant one summer afternoon. We thought we would go down to the creek instead. Moored alongside was a boat that had a dinghy tied to its stern. It was high tide, but we saw no fear as we climbed down the ladder which was on the side of the creek and clambered into the dinghy. We had great fun letting the dinghy drift out on the creek and then hauling ourselves back to the boat using the rope, imagining ourselves having a high sea adventure. Out of nowhere came some of the older boys who saw us playing merrily in the dinghy. They decided to have their own fun, so stealthily climbed onto the boat and untied the dinghy. We were unaware at first that we were completely adrift, but started to panic when we found we could not haul ourselves back to the boat. We started to drift further out into the creek away from the dockside, while the boys remained hidden, congratulating themselves on their splendid prank. We were now quite worried and were each trying to put on it brave face. Suddenly Nellie Scanlon, whose nickname was “old fashioned Nell” made the first move. Remembering her pretty coloured texts from Sunday school and having complete faith she announced “ If Jesus can walk on the water, so can we” and promptly stepped out of the dinghy, with total confidence. I was convinced she must be right and immediately followed her. The only walking our legs did was to the bottom of the creek – we then both started to claw our way to the surface. Spluttering and cursing I yelled “It didn’t bleedin work for us” to which Nell scathingly replied, “Well we can’t be ‘oly enough”. Mary Taylor, a brighter soul, called from the dinghy “Just as well you are not too ‘oly otherwise the water will sink into you and you will drown” With these words of comfort and the thought of drowning we both began to thrash about in the water. trying to keep ourselves afloat.

The boys came out of their hiding and along with Mary shouted words of encouragement to get us to keep treading water and to head for the ladder on the side of the creek, Progress was slow and the boys were very worried at this point that their prank could backfire. So someone rushed off to get my Mum, while the others leaned over the wall of the creek ready to pull us to safety as we neared the edge. One of the boys who was a reasonable swimmer jumped in and swam out to haul the dinghy and Mary back to the boat.

The boys came out of their hiding and along with Mary shouted words of encouragement to get us to keep treading water and to head for the ladder on the side of the creek, Progress was slow and the boys were very worried at this point that their prank could backfire. So someone rushed off to get my Mum, while the others leaned over the wall of the creek ready to pull us to safety as we neared the edge. One of the boys who was a reasonable swimmer jumped in and swam out to haul the dinghy and Mary back to the boat.

Mum was furious and gave me a thrashing for playing truant and then gave me another thrashing for nearly drowning myself – then she hugged me with relief. The worst punishment was dished out by the headmaster when he heard about the incident. We were not allowed to go on the outing to Theydon Bois and the 2d each that we had paid for the trip was to be forfeited. The next day all three of us stood in tears as the rest of the school went gaily off on their outing. Depressed and dejected we then went off to look for jobs to earn enough to repay our mums for the money we had “thrown away”.

One outing that was not such a treat was when we younger children had to go with our Mum to visit our Gran and Granddad who lived in Roscoe Street, Canning Town. We would walk the journey, taking about 45 minutes each way. Granny Nichols was a lovely old lady who made a fuss of all of us and did all she could to help out. Granddad Nichols however, was an old ogre and treated us as if he really hated us. He would pick on everything we did saying it was wrong, shouting and moaning at us the whole time. None of us children liked him and all but Giggy were afraid of him. He struck terror into Maggie and Steve in particular when they were younger. As soon as we were able to we stopped going to see him. Our Grandparents never came to our house in Orchard Place.

Granny Nichols, seen here possably at hopping.

Christmas though not an occasion of extravagance and expense as it is today, was still a highlight for us. We couldn’t buy a big tree or fancy decorations, but Giggy would always get something from Chrisp Street market, that had been left behind when the traders had packed up for the night. With great excitement, we would place our decorations made from bottle tops and silver paper, which we had spent weeks before in the making. There would be holly and mistletoe too, picked from the park. Mum would go to either Rathbone St or Chrisp St markets late on Christmas eve, where she would get a sack of 50 oranges for a shilling and traders would throw in any other pieces of fruit and nuts that they wanted to get rid of.

So on Christmas eve, we would hang our socks on the bedpost in anticipation. By morning they would be filled with an orange, an apple and some nuts. We would devour these with great delight and consider ourselves truly lucky. Granny Nichols always gave us each a bright new shiny penny as a Christmas treat. This was a real treasure and could be used to buy many wonderful things. As our father was a seaman every year we would get an invitation to a Christmas party at the Seaman’s Mission in Burnett Road, Poplar. The kids called it “Jack’s Place”.

Entertainment would be provided and everyone would sing songs. One year the MC asked if there was a boy or girl who would like to come upon the stage and perform. As quick as a flash I was up there – anything to get in the limelight. I did a tap dance (of sorts) and relished the applause – definitely a frustrated performer. To my great delight, I was given a gollywog as a special prize and this became my most treasured possession. It was a grand party and every child would be given a Christmas present at the end of it. This was the only present we ever received, there was no money spare for birthday and Christmas presents.

Mum also received a hamper from the Seaman’s Mission which helped to provide a special Christmas lunch for all the family at home. New Year’s day was also a holiday and all the school children throughout the borough would get a ticket for the “pictures”. There were two theatres in the Blackwall Tunnel area one was the “Grand” and the other was the “Pavilion”. There was also an Old-time music hall in Poplar High St called the “Queens”.

Bow Street school always seemed to be allocated tickets for the “Queens”. Here you could see a few old chorus girls doing a high kicking routine, but for me, it was 7th heaven. I felt that I was watching Hollywood starlets and would spend all my time afterwards practising the steps. For the majority of the Bow Creek gang, it was a ridiculous spectacle. When we went into the theatre we were each given an orange, apple and a marzipan fish. You can imagine what happened to the peel, cores and pips when the children had had their fill!

Every Christmas the local Factories used to make a collection to give all the school children a Christmas party. This really brought out the spirit of Christmas. Long tables filled with cakes, lemonade and little plates of jelly and fruit were laid out in the school hall. Party games such as musical chairs, pass the parcel and pin the tail on the donkey would be played with whoops of delight. Each child received a small packet containing a few sweets. This would be given to us by Father Christmas. Resplendent in a red gown and snowy white beard he would sit and wait for each child to sit on his knee. He would ask us if we had been good and of course we all said yes. The older boys would shout and holler saying it was only someone dressed up and would try to pull his beard or raise his gown. Despite this, I always had a special time at the party and even though Giggy was a ringleader for the unruly boys, he would later reassure me, in private, that the man had really been Father Christmas.

Later as I grew older my friends and I would go off on local outings by ourselves. A popular trip included walking up Leamouth Rd to the Canning Town Bridge and catching a half penny train ride to the East London Cemetery. We would take with us a bottle of tea and some jam sandwiches and spend the day there admiring the craftsmanship and reading the inscriptions on the headstones. We were always saddened if we found the grave of a child. Sometimes we took the tram or train from Canning Town station to the Woolwich Ferry where we would sail back and forth – sometimes running under the tunnel. Tunnel gardens at Blackwall was another favourite haunt.

.jpg)

One year when I was about ten Dolly and l went to Littlehampton for two weeks, this being our one and only real holiday. It was part of the Country holiday fund, which you paid into on a weekly basis, according to your means. We stayed with a local family, who were supposed to treat us like their own. Well if that’s how they treated their kids I am glad they weren’t my parents! Supposedly filling us with wholesome country food we were starving most of the time and talk about bossy. However, Mum must have been feeling reasonably flush, because she sent me a postal order for one shilling and sixpence. I felt very rich and was able to get some extra food to fill my tummy. We were taken out on a couple of outings other than that we played as we did at home.

A trip to Loughton Woods in Essex was always groaned at, “Oh no not lousy Laughton again” we would cry. However, any escape to the country was appreciated and much fun was had climbing trees and picking wildflowers.

Chapter 6 – Jobbing

All East end children did their bit to help the family coffers. Depending on whether or not they enjoyed school would decide whether they “jobbed” after school or played truant to earn a few extra coppers. Steve, my elder brother was a quiet, bookish boy, who enjoyed his studies. He would, however, go up to Blackwall Tunnel after school to sell newspapers and bring in a few extra shillings a week.

Toshing or dragging the river for odds and ends was very popular. All the children would go down to the causeway and collect driftwood and chalk. They would then go door to door. selling their wares. Giggy‘s barrow was a real boon for this work. The chalk was used for whitening the stone steps that led up to the front doors. Everyone was very proud of their white steps.

Another job the children did was “scurfing”. For this boys were employed to crawl into ship’s boilers that had become encrusted and chip away the deposits with a special hammer. A local rhyme about toshing ran:

So help me Bob

My Father’s a snob

My Mother takes in washing

My brother drives a carriage about and I go out toshing.

Giggy and I would often accompany Mum on the Green Line bus to Rainham for pea picking. We would get between 9d and a shilling for filling a 56lb sack. which was money hard-earned. At one time when Mum was ill, Giggy then aged 10 and me aged 8 boarded the bus by ourselves and went to pick the peas alone. We were quite confident as we had done the journey a number of times before. The work was back-breaking as all day we would be bent over the plants, plucking the pea pods from the stalks and filling the canvas sacks. These in turn became very heavy as we began to fill them and Giggy and I had to drag them down the lines. The sun beat down upon us the whole day. We were both happy though and in our element, preferring to be out in the fresh air rather than being in class. Pleased that we were doing our bit to provide for the family.

Other fruit picking jobs included apples and berries, plus potato and hop picking. All were hard work for little reward but as children we considered ourselves to be lucky to be able to do it. Of course, there were perks to he had, like filling your own basket with whatever you had been picking. This meant a supply of fresh fruit or vegetables, which could also be made into jams and pickles. One of the “jobs” that Mum did was to collect “parcels” from the neighbours and take them to the pawnshop for them. She had nothing left to pawn for herself, but most people had a little something that was worth a “few bob”. They trusted her and would give her a few pennies for taking the parcels for them. The pawnshop was still a stigma even for the Eastend folk, so it was worth giving someone a few pennies to do the job for you.

Other fruit picking jobs included apples and berries, plus potato and hop picking. All were hard work for little reward but as children we considered ourselves to be lucky to be able to do it. Of course, there were perks to he had, like filling your own basket with whatever you had been picking. This meant a supply of fresh fruit or vegetables, which could also be made into jams and pickles. One of the “jobs” that Mum did was to collect “parcels” from the neighbours and take them to the pawnshop for them. She had nothing left to pawn for herself, but most people had a little something that was worth a “few bob”. They trusted her and would give her a few pennies for taking the parcels for them. The pawnshop was still a stigma even for the Eastend folk, so it was worth giving someone a few pennies to do the job for you.

So every Monday morning she would carry the parcels up the Leamouth Rd to Willets the Pawnbrokers shop in Chrisp St. with its three shiny brass halls hanging outside. There she would pledge the goods for her neighbours. Mrs Wallington always gave Mum her husband’s gold watch for which Mum got her fifteen shillings. She would return on Saturdays to redeem the goods once the housewives had received their pay from their husbands. This was repeated most weeks and was the way the poor managed to survive and have enough food for the week.

The type of things they would “pop”, as pawning was known, would be best clothes or out of season clothes, shoes, jewellery and ornaments. If desperate it would be their wedding rings (substituting them with a cheap “Woolies” ring, so that their husbands didn’t notice). For some people, their personal possession spent more time on the shelves of the pawnbrokers than they did in the home.

Everything had to be wrapped up in a parcel and tied together. If you were lucky you had a sheet of brown waxed paper and string, which you would use over and over again. Otherwise, it would be newspapers or old rags that held your worldly possessions. When you gave in the goods the shop owner would write out a ticket. Willet had a special pen that had three nibs on at pole and he would write the tickets simultaneously. One was attached to your parcel with along straight pin, you were given another ticket, the final one being kept for his records. The shelves in the shop were stacked with an assortment of parcels of all shapes and sizes. They were stacked in numerical order. Set sums were paid according to the contents. If you got more than you expected, the joy was short-lived, as you had to find more when it came to redeem the goods.

Sometimes goods stayed pledged for a longer period. especially if your husband was at sea or working away. These then became harder to redeem as time went on and funds became harder to find. After six months if the goods were not collected the parcels would be unwrapped and the goods were sold in the Pawnbrokers shop. So it paid to keep a track of your tickets and to remember what was in each parcel. Another popular pawn shop was Pappernouies, down the marsh in Victoria Dock Road, Canning Town.

Mr Aspinall had a boat which he kept tied up on the Rivet Lea. next door to Fowler‘s factory. Every Sunday he would go shrimping at Leigh on Sea, at the estuary of the River Thames, taking some of the local men with him to help out. When my Dad was in Orchard Place he would go with Mr Aspinall and the crew to help catch the shrimps. On the way back they would boil the shrimps and as the boat came in a crowd would gather to buy his catch, as a special treat for their Sunday tea. Not only would Dad get a little cash for helping out on the trip but we would also enjoy a “shrimp tea” whenever he went out with the boat. Many locals had boats that they used for dredging for coal on the foreshore or salvaging timber from the river. Some had been made by their owners from condemned barges and lifeboats. Fishing was still one of the local occupations.

Granny Nichols did her hit to help us. using the huge mangle in her wash house. She would take in peoples sheets, boil them in the copper until they were brilliant white. Then pass them through the mangle. The pressure smoothed the linen sheets. so that they were wrinkle-free. Hung out immediately to blow in the wind and a final run through the mangle when dry, avoiding the tedious task of ironing them. At 2d a bundle, she would have a little cash to spare each week for Mum.